Japanese movies have often been very experimental and broken many boundaries and taboos. Their influence on the world of cinema is simply undeniable.

The biggest icon to come from Japanese film is easily Godzilla. It started with the movie Gojira in 1954 and has impressively gone on to over 30 Japanese installments as well as multiple American versions, notably in 1998 and 2014.

Godzilla is part of the kaiju genre which focuses on giant monsters. Other notable examples from Japan include Mothra and Gamera, and it’s inspired Hollywood movies like Pacific Rim as well.

The Godzilla series was mainly produced by Toho studios, the famous Japanese distributor and production company that was also involved with well-known anime from people like Hayao Miyazaki as well many of the biggest art house directors.

While the franchise has a reputation for being silly monster movies, Godzilla started with a deeper meaning. The original film came only a decade after the bombs were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Godzilla was created by nuclear radiation, and it also echoes the mass destruction of those events.

The Japanese version of Godzilla was most recently seen in the 2016 film Shin Godzilla, co-directed by Hideaki Anno and Shinji Higuchi, who both worked on the iconic anime series Neon Genesis Evangelion.

Modern film fans may be more familiar with Japanese movies through the horror genre. One of the most well-known and successful was Ring from 1998, based on a series of novels. It’s a solid film with a 97% approval rating on Rotten Tomatoes and it’s led to seven sequels. Ring was remade in America in 2002 and that movie got two sequels as well.

The next horror film to be remade for American audiences was Ju-On from 2000. Like Ring it started a lengthy franchise of 8 sequels. It’s not quite as good as Ring, but a perfectly fine film. Both series are supernatural horror and even crossed over in the 2016 movie Sadako vs. Kayako.

Other significant Japanese horror films of this era include two films from director Kiyoshi Kurosawa. The first big one was Cure from 1997 about people who commit murders they have no memory of afterwards. In 2001, he directed Pulse, which had a plot consisting of ghosts coming into the real world via the internet.

While Japanese horror reached the mainstream in this time period, there were notable works in the genre in prior decades as well, especially the 1960s, including Onibaba and Kwaidan.

Japanese horror movies often had storylines involving spirits, demons or other supernatural forces, but combined with social commentary. They take from folktales as well as Kabuki and Noh theater.

The nation of Japan has also made a huge mark in the world of art house cinema, especially starting with the Golden Age of Japanese Cinema in the 1950s.

This was kicked off in 1950 with Rashomon, which brought its director, the legendary Akira Kurosawa into the international spotlight. Rashomon won the Golden Lion, the top prize at the Venice Film Festival as well as an Honorary Oscar, and has earned a reputation as one of the best and most influential movies ever made. Its importance is largely because of its narrative structure, showing the same event from four contradictory perspectives.

Rashomon starred possibly the greatest Japanese actor of all time, Toshiro Mifune and was one of 16 times he worked with Kurosawa in easily one the best director-actor combinations. One was the masterpiece Seven Samurai, an almost three and a half hour historical epic that consistently appears on lists of the best films of all time, including multiple appearances on the top ten of the prestigious Sight and Sound critics poll.

It revolutionized action cinematography with the use of long telephoto lenses and multiple cameras, inspiring countless other filmmakers.

They also collaborated on Throne of Blood, based on Macbeth, and The Hidden Fortress, which is now famous for having directly influenced Lucas while writing Star Wars. Unfortunately, after Red Beard in 1965, they never worked together again.

These were all period dramas, a genre known in Japan as jidaigeki. But Kurosawa also made contemporary dramas, or gendai-gekis (hard g). While these don’t get as much attention as his historical films, they’re very intelligent explorations of social problems like crime or corporate corruption.

Kurosawa’s influence on the next generation is undeniable as many significant directors from the 1970s and 80s have a clear affinity for his work. Lucas and Francis Ford Coppola both helped fund his later movies and Martin Scorsese played Van Gogh in Kurosawa’s 1990 film Dreams. In my opinion, he’s clearly the most influential Asian director in film history.

Almost as influential and a contemporary of Kurosawa was Yasujiro Ozu. His cinematography isn’t as flashy as Kurosawa’s but no less masterful. Ozu’s style was calm, consistent, and very idiosyncratic, with camera movement being rare. He utilized low camera angles to prevent a human-like perspective and completely disregarded the 180-degree rule, unusually using the entire space to place the camera. Ozu’s camera is objective and besides in his early films, there are no POV shots or flashbacks.

He mainly avoided dissolves and wipes, but used so-called “pillow shots” as transitions. These shots serve no narrative purpose and often focus on landscapes or empty rooms.

Some good places to start with Ozu are Late Spring from 1949 and Tokyo Story from 1953.

While he had been making significant films in the 30s and 40s as well, director Kenji Mizoguchi was also active during the Golden Age. Like Ozu, his camera rarely moved. He used very long takes that often went on for minutes.

Mizoguchi made movies about social issues, often focusing on the suffering of women, including two films about prostitutes.

Japan’s cinema maintained relevance into the 1960s and 70s largely because of the Japanese New Wave movement. However, these filmmakers were starkly different from the old masters like Ozu and Mizoguchi.

Director Nagisa Oshima is associated with the Japanese New Wave and his most famous film is In the Realm of the Senses from 1976. It features unsimulated sex scenes as well as sexual violence and caused great controversy.

Also part of the movement was Shohei Imamura, the only Japanese filmmaker to win two Palme D’ors, one for The Ballad of Narayama in 1983 and one for 1997’s The Eel. Imamura began his career as an assistant for Ozu, but was critical of his style.

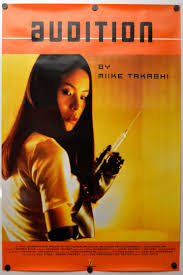

A more modern director who’s made a name in the art house world and mainstream films as well is Takashi Miike. Most in the west know him for extremely violent, bizarre works like Audition and Ichi the Killer. However, he also makes family films such as Zebraman and mainstream horror with One Missed Call.

He even freely mixes genres, as in Happiness of the Katakuris, which combines elements of musicals, comedy, animation, and horror. And he makes stuff like Visitor Q that defies categorization entirely.

Miike’s movies are sometimes quite gory and disturbing, and violence is often associated with Japanese film by Westerners.

A very famous example is Battle Royale from 2000, where a group of high schoolers are forced to fight to the death. It became highly controversial for its violence and unsettling premise. Battle Royale directly influenced Quentin Tarantino in Kill Bill and has a similar idea to The Hunger Games.

Also disturbing, but much more experimental is Tetsuo: The Iron Man, a 1989 cyberpunk film written and directed by Shinya Tsukamoto. The frenzied black and white body horror movie is often compared to David Lynch and David Cronenberg.

Of course, samurai films are a popular genre out of Japan, with a famous example being the Zatoichi series that began in 1962 and spanned almost 30 installments.

Another big samurai series is Lone Wolf and Cub, based on the manga of the same name and consisting of six films in the 1970s and two TV shows.

Japanese film is still going strong with directors like Hirokazu Koreeda, who won the Palme D’or in 2018 for Shoplifters.

You may be wondering why I haven’t talked about anime, but that would require a completely separate video and I’m sure many of those already exist.

Some of my favorite anime films include Akira, My Neighbor Totoro, Summer Wars, and the Evangelion rebuilds.

No comments:

Post a Comment